202407262106

Status:

Tags: Paed

Craniosynostosis

One of the most common craniofacial congenital abnormalities requiring surgery is craniosynostosis where there is premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures. This leads to a failure of normal bone growth perpendicular to the suture. Compensatory growth occurs at other suture sites and results in a characteristic abnormal head shape

isolated craniosynostosis : 80%

- usually simple

- typically involves single suture

- not associated with other abnormalities

- etiology is nongenetic

- majority probably being caused by intrauterine fetal head constraint.

syndromic craniosynostosis : 20% - usually complex

- multi-sutural

- often have identifiable genetic cause

- affect both skull vault & facial skeleton

- esp maxillary hypoplasia

- → exorbitism / proptosis

- → OSAS

- esp maxillary hypoplasia

- extra-cranial features

Syndromes a/w craniosynostosis - Crouzon

- Apert

- Pfeiffer

- Saethre-Chotzen

- Carpenter & Muenke (less common)

Both isolated and syndromic craniosynostosis, although predominantly the latter, can lead to raised intracranial pressure (ICP). ↑ICP can occur in 40–70% of syndromic craniosynostoses because of multiple suture fusion.

It can be due to - hydrocephalus,

- airway obstruction,

- .skull being too small for the brain (craniocerebral disproportion)

- abnormalities in the venous drainage of the brain

Most syndromic craniosynostoses show autosomal dominant inheritance

Mutations in genes coding for fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) are responsible for the most common syndromes

in Apert syndrome (one of the more severe forms of the craniosynostosis syndromes), the FGF binds to the abnormal FGFR 2 for a prolonged time, prematurely signaling for immature bone cells to differentiate and cause suture fusion.

Apert syndrome occurs in 1 : 65000 births. In this condition, bicoronal synostosis occurs, leading to brachycephaly with associated large, open anterior and posterior fontanels, which frequently connect. They can frequently be an associated cleft palate. Midface hypoplasia leads to airway problems and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Shallow eye sockets (exorbitism) can lead to corneal exposure and potential dislocation of the eyes in extreme circumstances

Apert syndrome can be identified by complex, symmetrical syndactyly, with fusion of at least the central three digits, which may allow antenatal ultrasound diagnosis.

Mutations in the FGFR 2 gene, located on chromosome 10, are also responsible for Crouzon and Pfeiffer syndromes and lead to a similar facial appearance

Surgical considerations

Classification of craniofacial procedures

Orthognathic surgery

Monobloc distraction

EOT

Emergency indications for surgery in craniosynostosis include the following:

• 1 Need urgently to protect the airway.

• 2 Need urgently to protect the eyes.

• 3 Manage acutely or chronically ↑ICP

Elective

early stage, between 3 and 6 months

- adv

- bone being soft & easy to bend & reshape

- brain is undergoing rapid growth ∴ will drive the growth of the cranial vault

- disadv

- ↑ risk of having to repeat the surgery during youth

- ∵ ongoing craniocerebral disproportion → craniostenosis

- ↑ risk to the child ∵ smaller blood volume

Older

- ↑ risk of having to repeat the surgery during youth

- Adv

- ↓ risks of reoperation

- disadv

- bone becomes too thick to remodel

- deformities can become too severe to correct

- older children lose the ability to ossify small craniectomy defects

- may need bone grafting when older

The three principles of elective calvarial surgery are as follows:

• 1 To prevent progression of the abnormality,

• 2 To correct the abnormality,

• 3 To ↓ risk of raised pressure that could occur if surgery is not performed

Pre-op

Airway

In Apert syndrome, midface hypoplasia and proptosis can make face mask ventilation difficult. Small nares and a degree of choanal stenosis cause high resistance to airflow through the nasal route, so these patients are obligate mouth breathers. Thus, face mask ventilation with a closed mouth can be challenging but simple airway maneuvres, adjuncts such as an oropharyngeal airway (OPA) or nasophayngeal airway (NPA) and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) are usually effective in relieving the obstruction. A significant proportion of children with Apert syndrome also have fused cervical vertebrae. However, intubation via direct laryngoscopy is successful in the majority of cases

An important caveat to this is children who have undergone frontofacial advancement. In these patients, intubation may be more difficult as a result of the altered relationships between the maxilla and mandible and reduced temporomandibular joint movement

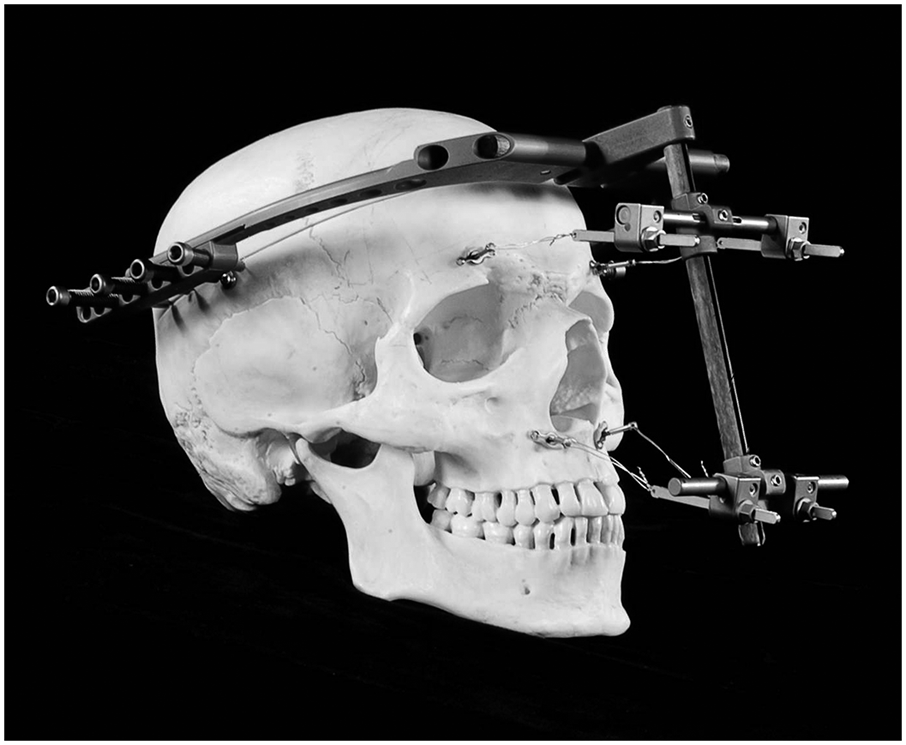

The presence of a rigid external distraction (RED) device should also be noted as it may make laryngoscopy awkward if not impossible.

Indications for tracheostomy

Indications for a tracheostomy:

- Severe and deteriorating upper airway obstruction

- Patients less than 1 year of age undergoing frontofacial monobloc advancement;

- Children undergoing extensive facial osteotomies in whom re-intubation may be difficult.

MDT decision

When a decision is made to perform a tracheostomy+

→ best done as a separate procedure at least 2 weeks prior to scheduled craniofacial surgery

→ ∵ well formed tracheostome

Resp

Apert syndrome:

- wheezing most common resp Cx

- ∵ stiff / vertically fused tracheal rings & accumulation of secretions

OSAS

Almost 50% of patients with Apert, Crouzon, or Pfeiffer syndromes develop OSA. The obstruction can occur at various levels but midface hypoplasia, causing a distortion in the nasopharyngeal anatomy, is a common feature. A timely intervention, such as insertion of a nasopharyngeal airway (NPA), may be indicated early in infancy, and such airways have an established role in the management of upper airway obstruction in these children

There is debate about the role and indications for tracheostomy in these children with upper airway obstruction, with some centers advocating insertion of a tracheostomy relatively early on in life and others favoring more conservative management, such as use of an NPA and CPAP.

Vicious cycle during sleep:

resp obstruction → ↑ICP → ↓CPP

-ve impact on neurological / cognitive development in the long term

Premed

caution ∵ airway obstruction & ↑ ICP

Intra-op

Induction

gas vs IV

Airway Mx

maintenance of a good airway may be challenging as a result of suboptimal facemask seal secondary to facial asymmetry, maxillary hypoplasia or exorbitism

Difficult laryngoscopy is unusual in patients with midface hypoplasia although children who have previously undergone corrective surgery may prove difficult to intubate.

Choice of ETT depends on type of surgery & positioning

e.g. RAE, reinforced, nasal intubation

Temperature regulation

important to commence warm air devices immediately, since induction and line placement can take a long time

Positioning

The modified prone position has also been called the ‘sphinx position’, as the patient is positioned prone with their head and neck extended so that the chin rests on a support. In a modified prone position (sphinx), hyperextension of the neck may result in spinal cord injury

protect at risk areas ∵ long OT

head-down position → venous bleeding

head-up position → gas embolization

Orbital injury can occur in surgery for both syndromic and nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. Corneal abrasions and irritation from cleaning solutions can be minimized by topical lubricant, and temporary tarsorrhaphy

may need Frost suture post-op

In children with syndromic synostosis, the orbits are at increased risk because of the associated proptosis. Another mechanism for ophthalmic injury is by direct orbital pressure; such pressure may result in damage to the optic nerve and retinal ischemia resulting in postoperative blindness. An acute presentation of direct orbital pressure occurring during surgery may be a vagally mediated bradycardia, most likely seen in FOAR surgery

Monitoring

A line

central line

ICP & CPP

Children with craniosynostosis (both syndromic and nonsyndromic) may have raised ICP. Normal reference values for ICP and CPP in children have not been studied. However, an ICP of <10mmHg in children is considered normal. It is generally accepted that an ICP of >15mmHg is defined as intracranial hypertension.

Normal CPP varies with age, and in the absence of published data, consensus opinion describes a CPP of 40–50mmHg in infants and small children

Intra-op complication / crisis

- accidental extubation / endobronchial intubation / severing pilot tube

- oculocardiac reflex → acute bradycardia

- VAE

- sudden major blood loss

- metabolic acidosis

VAE

Venous air embolism is a known complication during surgery for craniosynostosis surgery.

This apparently high incidence of VAE in infants may be due to rapid blood loss causing a decrease in CVP and so the development of a pressure gradient between the right atrium and surgical site favoring the entrainment of air. This means that an episode of hypotension precipitated by blood loss can be immediately followed by a VAE, and so there is potential for the diagnosis of VAE to be missed, and a failure to treat appropriately, such as flooding the surgical field and lowering the head position

The consequences of VAE include hypotension, cardiovascular collapse, and in the presence of a patent foramen ovale (which is present in 50% of children under 5years old), paradoxical air embolism with neurological sequelae.

Blood loss

Prolonged surgery (duration from the start of anesthesia to departure from theatre of >5h) is associated with increased blood volume loss (BVL)

There are surgical stages where sudden and extensive blood loss occurs. Knowledge of these stages enables the anesthetist to predict and prepare for hemorrhage. This occurs during initial scalp dissection and raising the periosteum

During the intraoperative period, direct assessment of BVL is difficult. The amount of blood collected in the suction is often minimal, with the majority of blood lost to surgical drapes and the surrounding area. Therefore, calculating BVL is often dependent upon assessing the required volume of fluid resuscitation and blood products transfused

During periods of hemodynamic instability, it is important to remain vigilant to other causes of significant intraoperative hypotension such as venous air embolism (VAE) and anaphylaxis.

Blood conservation strategies

Pre-op

- correct anaemia

- iron replacement

- EPO

Intra-op

- meticulous surgical technique

- ↓ venous bleed by head-up tilt

- adrenaline infiltration

- cell salvage

- acute normovolaemic haemodilution

- antifibrinolytics

- transfusion strategy

Controlled hypotension is a method employed in a range of surgical situations involving anesthesia to decrease blood loss; however, its role in craniosynostosis surgery is limited because of the concerns regarding cerebral perfusion pressure

One approach:

- coagulation profile checked once blood loss >1 EBV or 80ml/kg

- FFP 10ml/kg usually required after 1 EBV transfusion

- plt 5ml/kg usually required after 2 EBV transfusion

- (4ml/kg PC ↑Hb by 1g/dL)

- (measure Hb after transfusion of each 20ml/kg blood)

When BVL approaches 1.5× blood volumes, hemostatic blood products may be used empirically (such as FFP and platelets) in the absence of supporting laboratory results in an attempt to correct the anticipated dilutional coagulopathy

Acid base

BE corelates w/ blood loss & volume administered

Post-op

Analgesia

Example

- panadol 15mg/kg Q6H

- PO morphine 0.2mg/kg Q4H prn

- NSAID

- diclofenac 1mg/kg PO Q8H

- ibuprofen 5mg/kg PO Q6H

e.g. post-op morphine NCA in ICU

- background 20µg/kg/h

- bolus 20µ/kg

- 20min lockout

PONV

The implications of vomiting in children undergoing craniofacial surgery, apart from the general issues of delayed recovery and dehydration, relate to the increase in intracranial pressure that occurs during vomiting. This elevation in intracranial pressure could result in a cerebrospinal fluid leak, and possibly fistula formation

dexamethasone ↓PONV & ↓ swelling

hypoNa

present after any major pediatric surgery, but may be increased after craniofacial surgery. The cause of hyponatremia is likely to be related to anti-diuretic syndrome secretion or administration of hypotonic intravenous fluids.

Factors associated with an increased risk of development of hyponatremia include syndromic craniosynostosis, greater BVL and raised intracranial pressure preoperatively

References

Anesthesia for Surgery Related to Craniosynostosis A Review. Part 1

Anesthesia for Surgery Related to Craniosynostosis A Review. Part 2